№ 19 / 10.07.2023

Siarhei Bohdan

Introduction

Belarus has always been a Hinterland for Lithuanian, Latvian, and Ukrainian seaports, which have served as a sort of “gateway to the world” for it. Belarus’s ties with its neighbours have remained uninterrupted for centuries, save for the brief inter-war period. Therefore, the relationship that has evolved as a result of the lasting historical process is now breaking up before our eyes, causing devastating consequences for the entire region between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea.

Since it gained independence, and especially in the 2010s, Minsk has actively sought to grow transit flows related to the Belarusian economy and provide alternative routes to foster foreign economic connections via the seaports of the neighbouring countries. Of particular importance in this context was its endeavour to diversify crude oil supplies by sea, with respective efforts encompassing absolutely all the neighbouring countries. Diversification of crude oil deliveries envisaged supplies through the ports of Ventspils (Latvia), Klaipeda (Lithuania), Gdańsk (Poland), and Odessa (Ukraine). By the mid-2010s, Belarus had formulated a basic conceptual vision of its role on the continent as a link between the Eurasian and European integration blocs within the framework of the “integration of integrations” concept. Stemming from this was its policy pursuing transit development, promotion of transport services, and build-up of transport infrastructure.

According to the Concept for the Development of the Logistics System of Belarus until 2030 approved by the Council of Ministers of Belarus in 2017, Minsk intended to double its revenues from transit and transport services. The document outlined the country’s key priorities — the development of transit between Europe and China (including as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative), integration with the EU markets, promotion of logistics integration between the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and co-operation with global logistics companies. The framework documents were not the only impetus to Belarus’s transit role in various sectors, as it was encouraged by regional developments as well. Transit by rail and air increased following the conflict in the East of Ukraine, as Kyiv curtailed its relationship with the Russian Federation.

The escalation of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine had little effect on the strategic diversification projects implemented by Minsk up until the autumn of 2020.

However, since at least 2016, Moscow had insisted that Belarus redirect the transit of its oil products from the Baltic States to Russian seaports. To encourage the move, the Russian Federation offered discounts on the transportation of respective cargoes by the Russian Railways, but Minsk did not comply. In August 2017, Vladimir Putin personally demanded that transit of Belarusian oil products be reoriented. In December 2017, the Belneftekhim state-run oil concern announced the commencement of exports of some of its oil products via Russian seaports instead of those on the Baltic Sea, but even after that announcement, Minsk was in no hurry to redirect its commodity flows. Moreover, there were no technical possibilities for quick shifts. However, efforts to engage other regional states in diversifying energy supplies to Belarus and the Black Sea–Baltic Sea region failed, and Minsk was forced to yield. In early 2018, Belarus decided to close its consulates in Ukraine’s Odessa (originally opened in 2011 to help diversify crude oil supplies) and Poland’s Gdańsk.

In addition to that, circumstances turned out to be unfavourable for Minsk’s cooperation with Lithuania, a key country in terms of Belarusian transit. In the second half of the 2010s, a serious dispute arose between the two countries over the construction of a nuclear power plant in Belarus. Seeking to thwart the project, Lithuania put pressure on Minsk in all areas. It was at that time that Lithuanian politicians started making statements that co-operation with Belarus was undesirable and recommending private businesses to avoid Belarusian partners. For example, when trying to expand its export infrastructure in Klaipeda by purchasing a portion of a new terminal in 2019, Belarusian Potash Company (BPC) encountered administrative obstacles. The deal was perceived by Vilnius as running counter to national security interests.

Minsk’s relationship with Russia grew sour in the 2010s, adding to the cumulative effect undermining Belarus’s role as a regional transiter. Natural gas transit — more lucrative and politically important than crude oil transit — was the first victim. The Nord Stream pipelines empowered Moscow to deliver gas from Russia to Germany via the Baltic Sea, bypassing Belarus and other Eastern European countries. That was a significant blow to Belarus, as Minsk not only had enjoyed a tangible rent from the transit of Russian natural gas, but also used its ability to adjust those transit flows as a bargaining chip in political disagreements with the Kremlin.

It was not only gas transit that Minsk was losing. In spring 2016, the Russian government decided to organise a railway ferry crossing between the Russian mainland and its Kaliningrad exclave. That move ruled out Russia’s reliance on the countries of the region, including Belarus, for overland connections to the Kaliningrad Region. At the same time, Russia closed almost the entire border with Belarus to third-country nationals in autumn 2016, whereas in February 2017, it introduced border control zones along it.

Difficulties persisted in other areas as well. In October 2017, Lithuania and Latvia made an official decision to disconnect by 2025 from the unified regional energy system BRELL, created on the basis of the Soviet energy infrastructure in 2001 together with Belarus, Russia and Estonia. The decision was taken and implemented with the active involvement of the EU institutions. There were no negotiations with Belarus on the topic, although that break-up implied serious consequences for the region.

Although the EU and the neighbouring countries were de facto ignoring Belarus’s attempts to strengthen its independence by diversifying its external relationships and regional integration, Minsk continued to strengthen its transit position up until the 2020 election.

This was manifested, among others, in the commencement of alternative crude oil supplies to Belarus (which would open up opportunities for diversification of crude oil imports for other countries in the region). In January 2020, Lukashenka demanded: “We must achieve a situation where we buy 30% to 40% of oil from Russia, import 30% through the Baltics and the remaining 30% through Ukraine.” In 2019–2020, Belarus was receiving crude oil from Azerbaijan, Norway, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia via the Klaipeda seaport.

Geopolitical pivot of 2020: why all roads lead to Moscow from now on

Measures put in place to combat the coronavirus pandemic made a critical contribution to the disruption of transport connections, disintegration of the region and the subsequent escalation of tensions there. As early as the start of 2020, a massive severance of human contacts became obvious. Firstly, almost all countries in the region put in place epidemiological restrictions in border movement. Secondly, in March 2020, passenger transport by rail was suspended between Belarus, on the one hand, and Lithuania, Latvia and Poland, on the other. Before the pandemic, traffic with those three countries accounted for about 20% of Belarus’s total international transportation: according to the Ministry of Transport of Belarus, in 2019, rail passenger traffic with Lithuania reached 380,000 people, with Poland — 225,000 people, and with Latvia — 20,000 people.

The presidential election of August 2020 further accelerated disintegration and rupture processes in the region. A new wave of transit wars commenced, when on 28 August 2020, in response to the Lithuanian government’s sanctions against Belarusian officials, Lukashenka demanded that Belarusian cargoes be redirected in order to bypass Lithuanian seaports. This implied turning respective flows towards Russian seaports, even though the Russian Railways could barely cope with that new task to the full extent, and at that time Russia did not have sufficient available port capacities to handle exports from Belarus. A solution to some of those problems was for Belarus to build a new seaport in Russia. In September 2020, Lukashenka suggested that Putin should approve investing USD 3 billion left from the loan originally committed for the construction of the Belarusian nuclear power plant in a port facility in the Leningrad Region.

The redirection of Belarusian transit flows to Russia produced a profound impact on both Minsk and the neighbouring states. For example, in 2019, Belarusian cargoes accounted for 30.5% of the Klaipeda seaport’s combined shipments: 14.1 million tonnes out of 46.3 million tonnes. This compared to over 9 million tonnes of cargoes in 2013 and almost 15 million tonnes in the record-breaking year of 2018.

At the same time, Minsk began to refocus its cargo transit by land. As he met with the State Customs Committee Chief Yury Sianko on 5 October 2020, Lukashenka said: “Almost 40% of trucks have come from Lithuania and Latvia this year. ... What does the Customs Committee think about redirecting these cargoes? What about the development of our own logistics centres? We have created powerful logistics centres. But many services, including for our business and for the EAEU countries, are still supplied in Lithuania. We can provide these services to these carriers in Belarus.” Furthermore, at the start of September 2020, the Belarusian authorities intensified inspections of transit cargoes travelling from Lithuania through Belarus, which increased delivery time.

Nevertheless, even though Minsk reacted to the pressure of the neighbouring states, it was in no hurry to break up ties and completely redirect its transit flows, holding onto its strategic diversification project to the last.

On 6 October 2020, a new — and probably last — tanker with Azerbaijani crude oil for Belarus arrived in Odessa, the sixth one in 2020. Further, in September, Belarusian state-owned companies announced plans to import non-Russian oil via Poland and Ukraine, whereas in October, Belarus started building the Homel–Horki pipeline, a connection between the northern and southern branches of the Druzhba pipeline, which would enable the two Belarusian refineries to receive non-Russian oil via both the Baltic Sea and Black Sea ports. In December 2020, the Belarusian side routinely extended the contract for crude oil transit to the Belarusian refineries from Odessa.

Experimental air blockade of an entire country

In the wake of the August 2020 election in Belarus, as Lithuania and Poland offered heightened support for the Belarusian opposition amid newly imposed EU restrictions against Belarus, official Minsk was naturally encouraged to seek closer ties with the Kremlin. On 19 February 2021, a Belarus–Russia agreement was signed on the transhipment of Belarusian oil products exported to third countries. Russian Transport Minister Vitaly Savelyev called it a “historic” one. The pivot was massive: Belarus agreed to start transhipments of more than 9.8 million tonnes of cargoes per year in Russian seaports on the Baltic Sea in 2021–2023. The shipments were urgently diverted as early as from 5 March.

Belarus also faced increasing challenges with transit by road. Obstacles had mounted even before the migration crisis. Lithuania unofficially started to limit transit through Belarus around March 2021, citing various technical difficulties. Since then, Vilnius has attributed the persistently acute problems with the passage of trucks across the Belarus–Lithuania border to the reconstruction of checkpoints, equipment failures, etc. The State Border Committee of Belarus stated that “the congestion problems on the Belarus–Lithuania section of the border have been there for a long time, even before system failures and renovation of checkpoints.[…] the Lithuanian side permanently fails to work to its full capacity, ignores agreements.[…] half of all emergency situations on the border between Belarus and the EU, which are related to the clearance of vehicles, are caused by the operation of the Lithuanian checkpoints.”

Whether or not these statements are true, since March 2021, the capacity of Lithuanian checkpoints has remained limited, albeit subject to certain fluctuations. This caused problems at other parts of Belarus’s state border, as the border with Lithuania was the most important direction for Minsk’s foreign relationships due to the proximity to Vilnius with its airport, access to the sea, and the border dividing the historically integrated Vilna region.

It was in that atmosphere that an incident occurred on 23 May 2021, when a Ryanair flight made an emergency landing in Minsk, after which its passengers Raman Pratasevich and Sofia Sapeha were arrested. In response, Lithuania was the first country to discontinue air communication with Belarus on 24 May, banning all flights to and from Lithuania flying through Belarusian airspace. On 25 May, Latvia and Ukraine followed suit, while other countries suspended flights through Belarus and banned Belavia flights from their airports. On 4 June, the EU officially closed its airspace and airports to all Belarusian aircraft.

These measures as good as ousted the national air carrier Belavia from the air transport market, which benefitted Russian air carriers. Moreover, the decision became a step towards a revision of the air transport regulations in place at that time. The leading industry organisation, the International Air Transport Association (IATA), criticised the move, noting that “banning European aircraft from using Belarusian airspace is a politicization of aviation safety.” IATA stressed that it condemned the actions of the Belarusian government, but two wrongs do not make a right, and the prohibition should be rescinded.

The disproportionately harsh response to the incident is obvious if one compares a number of similar forced landings. It is emblematic that even after the Ryanair incident, similar cases never provoked such a harsh reaction as the air blockade of a country, for example, the forced landing of a Khartoum–Istanbul flight on 15 January 2022 at Egypt’s Luxor International Airport and the subsequent arrest of Egyptian opposition activist Hossam Menoufi Mahmoud Sallam, an Egyptian and British citizen.

In early December 2021, the EU adopted sanctions against 17 individuals and 11 companies from Belarus accused of “organising illegal migration”, including the national airline Belavia. This further narrowed the transport capacity of Belarusian firms and increased dependence on Russian carriers. Immediately after the new sanctions were adopted, Lithuanian customs, citing EU sanctions, returned a cargo with equipment for Belavia’s aircraft to France.

The air blockade of Belarus is an unprecedented step in contemporary history. No country has faced anything like that in recent decades outside of armed conflicts.

These measures taken by the EU have fatally undermined the capability of Belarusian carriers to transport independently, without the involvement of Russian counterparts. They had a dramatic impact on regular citizens as well: many people had to reroute their foreign trips to travel through Russia and engage Russian companies. At the same time, the air blockade never compelled the Belarusian government to meet any of the demands of the opposition and its foreign allies.

Migrants — an excuse or a reason?

In response to the air blockade and the EU’s decision to halt co-operation with Belarus, Minsk refused to do the EU border protection “spade work”: it stopped keeping potential illegal migrants from approaching the EU borders. The resulting migration crisis once again became an excuse, rather than a real reason, for disproportionately harsh sanctions, which put a cap on Belarus’s foreign relations in all spheres. At the same time, the flow of migrants, even at its peak, remained negligible compared to those at the EU’s southern borders. Nevertheless, the neighbouring states immediately militarised the migration issue, started building walls along the border, restricted access to the border for citizens and the media, and took a number of other unprecedented measures.

Even before the migration crisis erupted, Belarusian potash was faced with increasingly harder access to seaports. Lithuania had restricted it since 2020. Minsk began looking for alternative export routes via the Russian Federation and started building its own port facility near St. Petersburg in the second half of 2021. The new terminals built for potash exports are scheduled to become operational in 2023. In early September 2021, the Lithuanian customs disallowed the shipment of spare parts for BelAZ trucks to Chile via the port of Klaipeda, citing the EU’s sanctions and the “dual purpose” of the dump trucks. The cargo was probably eventually confiscated. In late November, the situation was repeated as Lithuania returned to Belarus a cargo of spare parts for BelAZ trucks bound to Bosnia and Herzegovina, again on the pretext of sanctions.

In response to limited cross-border movements, the Belarusian government introduced mandatory navigation seals to be used by trucks coming from Lithuania starting 30 August 2021, which caused Lithuanian carriers to incur additional costs. The neighbouring countries, for their part, closed crossings on the border with Belarus. Specifically, in November 2021, Poland closed the Bruzgi–Kuźnica border crossing.

War and transit

By early 2022, Minsk had encountered serious restrictions and bans on the transport and transit of both cargoes and passengers. Belarus found itself in a semi-blockade maintained by all of its neighbours except Russia. In January 2022, Vilnius decided to stop transporting Belarusian potash fertilisers through its territory altogether from 1 February. The Lithuanian government acted on its own initiative, as the U.S. and EU sanctions did not require Vilnius to take such measures at that time.

The semi-blockade status and Minsk’s resulting reliance on Russia for all of its foreign relationships compelled the Belarusian government to make unprecedented concessions to Moscow.

As a consequence, when the war in Ukraine broke out, the Russian units staying in Belarus were involved in corresponding military operations.

To somehow make up for the growing dependence on Russia in its relations with the outside world, Minsk took a few steps. Firstly, it diversified export/import routes within Russia (using various ports) and started building its own port infrastructure. In March 2022, Lukashenka announced (and Putin later confirmed) that in two years, Belarus would have “its own ports” on Russia’s Baltic coast. Minsk is planning to concentrate its imports and exports at “its own” seaports in Russia. However, no ports in north-western Russia can become a worthy alternative to the Baltic ports, as they are too shallow for large ocean-going vessels. Instead, cargoes need to be reloaded onto smaller feeder vessels in Western European harbours and then transported to Russia. However, due to the sanctions and decisions made by European ports and global shipping lines, nearly all major shipping lines have refused to work with Russia. Therefore, Minsk considers working at the ports of the Murmansk region of Russia and building a port there to gain access to the ice-free Kola Bay with direct access to two oceans.

Secondly, Belarus attempted to prevent border closures in the region. After several years of experimenting with visa-free entry of foreign citizens via Minsk National Airport, in 2022, a visa-free regime was introduced for citizens of neighbouring countries arriving in Belarus by land. This practice was further expanded and Belarus offered Polish citizens a visa-free regime at all checkpoints for the period from March 2023 until the end of the year.

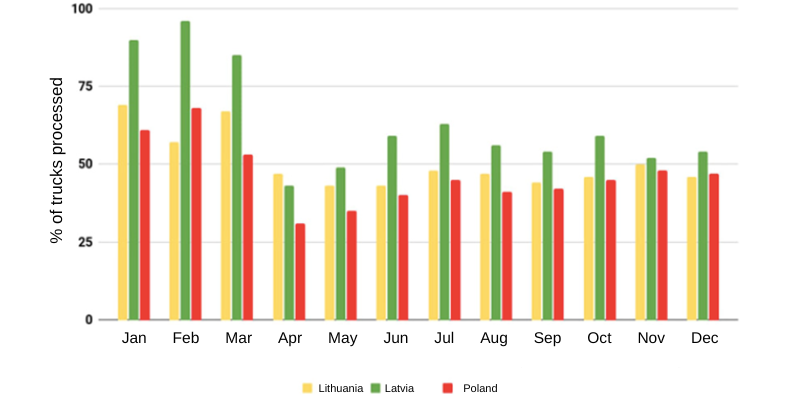

Nevertheless, the blockade tightened along the entire perimeter of the borders after February 2022. In addition to the severance of economic ties between Belarus and Ukraine after the outbreak of the war, the EU imposed new sanctions on Belarus, including transit restrictions. This was part of the economic war waged against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine, rather than a realistic plan to persuade Minsk to change its course. The tacit restrictions on the passage of trucks fluctuated depending on the market environment, but generally tended to increase (see Chart 1). For example, in mid-February 2022, just before the war, Lithuania and Poland processed only 60% of the daily officially agreed number of trucks. However, by mid-April 2022, the figure had dropped to less than 40%, according to the State Border Committee of Belarus.

Chart 1. Processing of trucks by the EU countries in 2022, % of the agreed number

Source: BelTA

On 8 April, the EU banned companies registered in Belarus and Russia from freight transportation through the territory of its member states. Minsk responded by restricting the entry of heavy trucks from the EU into its territory, only allowing them to go to recoupling and reloading stations, from where cargoes are transported only by Belarusian or Russian firms.

The timeframe of restrictions applied to road freight transport can be reconstructed based on statistics published by the State Border Committee. There are no indications that these data are false, nor do they contradict other reports on the situation at the border, while neighbouring countries do not publish any alternative data. It appears from the analysis of these data that Poland’s position was the toughest, whereas Latvia is the country that sought to act in a constructive manner.

Limitations of road freight transport became a serious blow to the Belarusian state and society. In the early 2020s, heavy truck transport was a developing industry, ranking second after IT in Belarus’s export of services. The Ministry of Transport estimates that the value of transportation services rendered to customers hiked by almost 40% to USD 4.3 billion year-on-year in 2021, which was the fastest reported growth in the history of the industry. Road transport companies accounted for 76% of the combined growth. Presumably, most of the business was associated with transportation to and from the EU. Disruptions of shipments caused not only an economic downturn, but also forced Belarusians to refocus towards Russian, Chinese and other non-Western consumers.

Disagreements with the EU evolved from political and ideological to cultural as well.

The Belarusian side made at least one demonstrative step in the opposite direction, allowing road carriers from the EU to transport goods through the territory of Belarus from 10 October, but the move was not reciprocated.

In parallel, the legal framework for co-operation at the border, in particular concerning traffic flows, was being dismantled. On 18 January 2023, the Lithuanian government denounced the agreement of 2006 on the principles of cross-border co-operation. According to the Lithuanian Ministry of the Interior, the implementation of the agreement is impossible in the current geopolitical situation and in the near future. The document envisaged arrangements on the movement of vehicles and passengers across the border, as well as assistance at the border in case of natural and man-caused emergencies. On 16 February 2023, Lithuania unilaterally terminated the agreement of 4 November 2019 on cooperation with the customs and border guard services of Belarus, which ensured smooth traffic flows across the border.

Checkpoints were also shut down, invariably causing a scandal. For example, the operation of the checkpoint in Bobrowniki ceased quite unexpectedly: on 9 February 2023, the Polish authorities announced its suspension from 14:00 on 10 February. The Polish Minister of the Interior cited state security concerns. After that, only one crossing point was left on the Belarus–Poland border for trucks — Kozlovichi–Kukuryki, whereas Brest–Terespol is now the only checkpoint for passenger vehicles. In response, on 17 February Minsk applied restrictions to Polish-registered trucks, allowing them to enter and exit Belarus only across the Belarus–Poland border. This led to further escalation when the Polish side allowed only EU- or EFTA-registered trucks to cross the border through the Kozlovichi–Kukuryki checkpoint from 21 February, again citing security concerns.

Severe restrictions of traffic flows followed, fuelled by corporate sentiment in Poland. At the end of February 2023, the Ministry of Infrastructure was urged by Polish international transport associations to start comprehensive inspections of transport companies with Belarusian and Russian capital registered in the country. On 1 June, Warsaw completely banned the entry of trailers with Belarusian licence plates into the country, thus stopping Belarusian road carriers from using the recoupling scheme to maintain at least some road freight traffic.

The relevance of disrupted freight traffic by road increased amid mounting obstacles to railway communication.

The neighbouring countries refused to restore passenger rail services after the pandemic ended. On 30 June 2022, Lithuanian Railways said that there were no plans to resume passenger traffic with Belarus in 2022 or 2023, “taking into account all circumstances.” Although all COVID-19-related restrictions had been removed by the Polish Ministry of Infrastructure in spring 2023, rail traffic never resumed. The Polish side cited tense relations between the countries.

At the same time, restrictions still apply to the volume of railway freight traffic, especially on the Lithuanian side. According to a report by the Ministry of Transport of Belarus, “in January [2023], on average, one or two trains passed through Stasylos–Benyakoni every day, and only about six or seven trains through Hudahai–Kena, with the established norm of 12 trains in each direction.” On 15 February, it was announced that the Lithuanian government decided to suspend the traffic of freight trains from Belarus to Lithuania via the Stasylos border crossing point. The official reason is the modernisation of the checkpoint to combat smuggling, which will continue until the end of 2024. According to the Lithuanian customs authority, the decision was caused by “major flows of contraband transported by trains from Belarus and the associated increased threat to the national security of Lithuania.” The authority cited statistics that Stasylos accounted for 87.6% of the total volume of contraband by rail from Belarus to Lithuania discovered last year. Freight trains can now only cross the Belarus–Lithuania border via the Hudahai–Kena border checkpoint.

On 1 March, LTG Cargo, Lithuania’s largest shipping company, in association with the state authorities, started to apply a stricter system of customs inspections of cargoes by tightening its requirements to the composition of supporting documentation and deadlines for submission. The company relies on a “zero risk” approach “in compliance with EU, U.S., UN and other sanctions.” As a result, throughout March–May, LTG Cargo rejected 1,339 out of 6,636 requests for cargo transportation, and 562 of the rejected requests pertained to carriage to/from Belarus. As the Lithuanian side admits, some requests were turned down based entirely on the alleged belonging of cargoes to categories subject to sanctions. It is forbidden to export crude oil and oil products, raw materials for the food industry, construction materials, chemical and mineral fertilisers, as well as technical equipment via the Lithuanian Railways.

When it comes to rail transport, Lithuanian restrictions apply to state-owned companies, which are the main taxpayers and sources of funds to finance social expenditures in Belarus. Also affected are civic cargoes that are important for international food security (such as fertilisers). Moreover, as a result, Belarusian products are not only driven out of world markets, but replaced with Russian equivalents, which are objectively easier for Russia to export via its own well-developed port infrastructure.

The restrictions that Lithuania imposed on railway transit between Belarus and the exclave Kaliningrad Region should be noted separately. They deprive Belarus of the opportunity to use Kaliningrad for access to the sea.

Conclusions

The sanctions against Belarus and entire sectors of its economy expectedly failed to compel Minsk to comply with the political demands of the Western countries. However, what they did instead was to drive the region into poverty and push Belarus into the arms of Moscow. Paradoxically, many sanctions were imposed on Belarus for Russia’s actions while further limiting Minsk’s autonomy from Moscow. Promoting democracy and ensuring prosperity in the region is clearly incompatible with this approach.

It makes sense to view the events that have led to the growing semi-blockade of Belarus as a single process in which the governments of neighbouring countries have restricted communications with Belarus. Limitations imposed on road carriage brought about more restrictions of rail transport and air services, and it has been true the other way round. Therefore, the air blockade was not a separate happening, but a follow-up of the previous measures. Furthermore, decisions made by individual countries complemented each other, since those countries de facto acted as a single EU/NATO bloc.

The large-scale restriction of land transit of a land-locked country constitutes a serious precedent in international law, as it means a revision of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982 (LOSC). Article 125 of the Convention establishes the right of access to and from the sea and freedom of transit for land-locked countries. The restrictions imposed by the neighbouring states on Belarus’s relations with third countries under the pretext of sanctions amount to a consistent gross violation of the convention. Essentially, the relevant norms of international law are being revised. The limitations on Belarus’s access to the sea are aggravated by a comprehensive air blockade.

This situation entails fatal consequences for Belarus and the entire region, with some aspects being unprecedented in contemporary world politics:

1. The population of Belarus is subjected to arbitrary mass punishment manifested in the artificial undermining of the economic foundation of its welfare. Some of the restrictions, such as those denying regular citizens of Belarus the right to cross borders or benefit from the financial infrastructure of Western countries are absolutely unprecedented. They had never been applied even to countries subjected to the harshest sanctions (e.g. Iraq, Libya, and Iran).

2. There are no indications that such arrangements contribute to the political democratisation of Belarus. In reality, the effect is quite the opposite. A perfect correlation is obvious between the imposition of sanctions and blockades and the decline of alternative political activities in the country. Attempts to attribute this decay solely to repressions cannot account for the more detailed dynamics of political activism. The sanctions and blockade directly contribute to the disappearance of alternative political initiatives inside Belarus and demolish the political and economic basis of socio-political pluralism.

3. This situation calls into question the very survival of Belarus as an independent viable state. The specific transport- and transit-related decisions made by the EU states since the spring of 2022 stem from the refusal to recognise any differences between Belarus and Russia. They lead not only to the delegitimization of the actually existing Belarusian state, but also expectedly push Belarus even deeper into the sphere of influence of Russia, against which the Western countries are waging an uncompromising yet verbal war. The blockade encourages Belarus’s absolute dependence on Russia in all areas, including relations with third countries. It also implies the severance of Belarus’s centuries-old historical ties with seaports in the neighbouring countries, populations of the border regions, as well as negative repercussions for the environment.

4. The sanctions and blockade against Minsk essentially destroy the political and economic foundation of the Baltic–Black Sea region as a historically established community. This is happening through the rupture of the fabric of interpersonal and business relationships, undermining of mutual trust, and militarisation of international relations in the region. As a result, the region is experiencing decline and damaging its own development prospects, as no equivalent ties are being built — even bypassing Belarus and Russia — to make up for the rupture of the key old communications.

Siarhei Bohdan

PhD in Political Sciences; member of the Minsk Dialogue Expert Council