Comment № 37 / 11.12.2019

Dzianis Melyantsou

The concept of neutrality and its varieties is studied in sufficient detail in the theory of international relations. Neutrality may be permanent or temporary. It may be the result of an agreement between great or regional powers and secured by international agreements. But it can also be declared in domestic legal instruments, or be the result of a convention of political elites.

In case of classical neutrality, if a war breaks out a neutral state does not take sides in the conflict, while maintaining contacts with all belligerents. Peacetime neutrality means non-affiliation with military blocs. All the while, the state can have powerful armed forces and take part in peacekeeping operations abroad. This is known as armed neutrality, Sweden being the case in point.

It is important to emphasise, however, that the neutrality of each neutral state is a unique phenomenon, the grand total of many factors: historical, cultural, geopolitical, domestic ones, etc. Each state paved its own way towards neutrality, and there may be great variability in the way neutrality is manifested in each case.

How applicable are these concepts to Belarus?

In the case of Belarus, we, of course, cannot talk about neutrality in the classical sense of the term. Belarus is not a non-aligned state. It is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization and, by virtue of its obligations, it will have to side with its allies in the event of external aggression against any of them. Nor is its neutral status formally laid down in its legislation. Article 18 of the Constitution only declares Belarus’s striving for neutrality. However, there is no developed strategy or national program to achieve a neutral status in practical terms. Belarusian officials avoid using this term in relation to the foreign and security policies of Belarus and never trigger discussions regarding the possibility and desirability of implementing a constitutional provision on neutrality.

Nevertheless, in real Belarusian foreign and security policies, one cannot but notice elements that are increasingly shaping a unique model of neutrality, which we will call a situational one.

Situational neutrality at work

Thus, in the foreign policy, neutrality was manifested in fundamental adherence to the international law and in specific steps taken by Belarus. In particular, in the non-recognition of the independence of Abkhazia and North Ossetia, the non-recognition of the legality of the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the condemnation of the US and Russian withdrawal from the INF Treaty. Minsk also offered its services in resolving the conflict in the east of Ukraine and became the venue for numerous conferences and negotiations aimed at de-escalating the international tension.

In the military sphere, despite pressure from Moscow, Belarus adamantly refused to deploy a Russian air base on its territory, did not support Russia's operation in Syria and continued to build its own army and defense policy assuming a possibility of threats emerging anywhere along its border. These steps were analysed in detail in a recent study by Sergei Bogdan and Humer Isaev, so we will not dwell on them here.

There is an obvious connection between situational neutrality and the officially declared multi-vectored policy, which has similar rationale – that is, minimising risks for the country in the face of increasing international uncertainty and the international law being ignored by major actors. At the same time, it is vital for Belarus to maintain close economic cooperation with the opposing forces: Russia, the European Union, and Ukraine.

All of the above causes political rhetoric (especially in the media) that Belarus is trying to have its feet in both camps and even ignores its commitments to Russia. Which is neglectful of the fact that the obligations under the CSTO and the Union State stipulate joint action in the event of external military aggression, but by no means require Belarus to uphold all the Kremlin’s foreign policies and military actions in peacetime – especially, the ones detrimental to its own national interests and not coordinated by the Russian leadership with their allies.

Thus, we establish, that situational neutrality is a peacetime strategy generated, in many respects, by the existing issues in allied relations with Russia, and not by the wish to create such issues.

At the same time, in its foreign and defense policy, Minsk takes into account Russia's interests and the possible risks borne by not taking these interests into account. Therefore, Belarus has never questioned its membership in the CSTO and, in general, its cooperation with Russia in the field of security and defense. This aspect should be recognized as another important component of the Belarusian version of situational neutrality.

This seems to explain the desire to avoid both the formulation of a documented strategy or a programme to achieve even such a limited neutrality, and a broad public discussion with the use of the very term "neutrality". Belarusian situational neutrality is thus a de factoneutrality and cannot be considered a legal concept.

Situational neutrality drivers and legitimacy

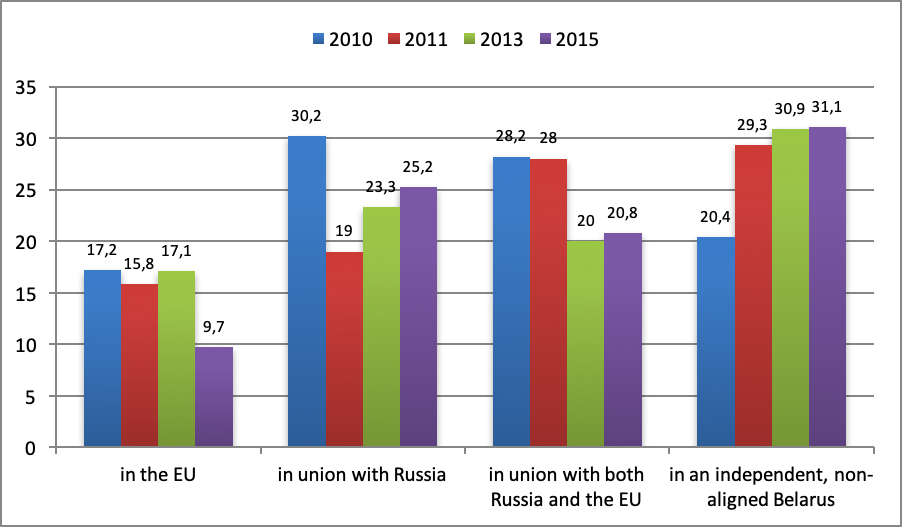

It is also important to note that the driver of the Belarusian take on situational neutrality was not only the external configuration of international relations and the balance of forces in the region, but also the state of the Belarusian nation. According to a series of surveys by the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies (BISS) in 2010-2015, there has been a steady increase in population support for the non-aligned status of Belarus.

So, choosing from four different options for the country's foreign policy orientation, in the 2015 survey, the majority of respondents (31.1%) would rather see a completely independent Belarus outside any international unions. Compared to the 2010 survey, the popularity of this option grew by 10.7 percentage points. Over the same period, the attractiveness of EU membership decreased by 7.5 percentage points, the alliance with Russia – by 5 percentage points, and the parallel union with the EU and Russia – by 7.4 percentage points.

These data, consistent with the results of many other opinion polls, can be used to argue that situational neutrality is not a random sequence of tactical steps taken by official Minsk to respond to externalities. This is, among other things, a reflection of the deeply-rooted changes in Belarusian public opinion, which began to manifest themselves noticeably as geopolitical tensions around Belarus started to build up. Therefore, it can be argued that the model of situational neutrality has meaningful foothold in the public awareness and, accordingly, has domestic legitimacy.

Chart 1. Changes in the responses to the question on «You would rather live in…».

Source: Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies, 2010-2015

As for the foreign legitimacy of the situational neutrality of Belarus, it is based mainly on the “good offices” offered by Minsk to resolve the Ukrainian conflict. And in broader terms – on the peacekeeping initiatives that Belarus has generated in recent years. This includes also the idea of a large-scale high-level international dialogue to develop the new rules of the game in the field of security (Helsinki-2), and the proposal of a declaration on non-deployment of the short- and intermediate-range missiles, and the regional confidence-building measures, as well as the fact that Minsk has served a platform for expert discussions on security issues.

However, the sustainability of the Belarusian situational neutrality requires one more crucial thing. It should be based on the interweaving of the interests of the most important international actors within Belarus.

The assets and projects of Russia, China, Germany, France, the UK and the USA need to be balanced in such a way as to make any destabilisation of Belarus unacceptable to them. So far, this process is only in early stages, but it seems to be vital not only for stabilising situational neutrality, but also for generally maintaining the sovereignty of the country.

Now, to recap.

Situational neutrality is a policy in the field of international relations and security, expressed in non-alignment with any of the conflicting parties in peacetime and the desire to help resolve international conflicts in order to create a more secure international environment. In the case of Belarus, situational neutrality is undeclared and happens de facto. Moreover, it is legally grounded by a constitutional declaration of striving for neutrality, as well as significant public support within the country.

Dzianis Melyantsou - Belarus Foreign Policy Programme Coordinator, Minsk Dialogue Council on International Relations.

The publication is supported by the Belarus Office of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (Germany). The content of the publication represents the views of the author only.