07.10.2019

The region’s status and security hazards

Eastern Europe and the entire European continent have entered a precarious and unpredictable phase of their history. Confrontation between the most influential international actors and the collapse of the foundations of strategic stability (the disarmament regime) threaten to escalate into major warfare, with a high probability of Eastern Europe becoming the battlefield. War has transformed the system of international relations so many times throughout history, and this can be attributed in part to states failing to adapt the rulesof conduct and mechanisms of their implementation in proper time.

The collapse of the post-war Yalta-Potsdam international system is underway and no new international regime has been put in place to effectively reflect the current balance of power. International organizations have limited capabilities for deterring great power confrontation.

Confrontation between Russia and the West prompts many researchers to draw parallels with the Cold War. As during the Cold War, in addition to geopolitical confrontation, there is also a conflict between value systems, although it has not reached the same depth and scope as in the period from the 1950s through to the 1980s. Russia and the West have reduced contacts in the economic, political and military spheres.

At the same time, there are numerous important differences. First, Russia is no longer an actor with the degree of influence that the Soviet Union used to enjoy and has a limited toolkit to implement its foreign policy. Second, unlike the Cold War, national decision-making at the operational level is often out of balance: there is no single center for deliberate decision-making, and, in some cases, medium-level orders have the potential to bring about a serious escalation of tension. Third, new technologies have changed significantly the very character of interpersonal and interstate communication.

The system of international relations is going through a transformation from its previous state into something new.

The world is in a state of “critical disjuncture” as a result of the breakdown and erosion of previous regimes. However, the fact that the key players have nuclear arsenals still keeps them from sliding into a new all-out war.

At the same time, the likelihood of an isolated kinetic clash resulting from unintentional actions or the willingness of states to take additional risks to demonstrate their “red lines” to opponents is increasing. The decay of strategic stability and the absence of normal dialogue between geopolitical rivals make this situation particularly dangerous. The East European region already has a hotspot in Donbas. Following the Minsk agreements (Minsk-2) its intensity can be characterized as low, but this could change at any moment and thereby critically alter the level of regional security.

The skeleton of a new system is not yet discernible and the current situation may continue for a while. The ongoing dissolution of the international security system makes crises more likely, especially when traditional channels of interstate communication have become inoperable and when non-state discussion platforms have become instruments of information warfare providing a forum for competitors seeking to expose their opponents. These system characteristics and challenges during this period of “critical disjuncture” are especially perceptible in Europe. Although the relationship between Russia and the West will not be the main driver in shaping a new system of international relations, it remains crucial to the European security architecture.

Analysis of events in Georgia, Syria, Ukraine and Turkey suggests that important geopolitical players have a poor mutual understanding of each other’s “red lines” in international politics. This renders both international security and strategic stability fragile. Where security is compromised and stability is disrupted, the probability of escalation into a military conflict cannot be discounted. Any failure to accommodate other actors’ interests, failure to comprehend threat perceptions, underestimation of a partner, and growing distrust have become the new normal for contemporary international politics. The case of Ukraine has demonstrated that the sense of vulnerability can trigger active military operations and, in turn, a regional crisis of a scale unprecedented since the end of the Cold War.

The INF Treaty and the breakdown of strategic stability

Following the U.S. withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty) in 2002, the termination of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) landed a second crushing blow on the arms control system and global strategic stability. For all its drawbacks, the INF Treaty had been a cornerstone of the nuclear arms control system, and many analysts think that the withdrawal of the U.S. and Russia from the treaty brings the world closer to nuclear warfare. Both the U.S. and Russia have already officially started developing previously-banned arms.

In this context, the American test of a ground-launched cruise missile with a range of more than 500 km on August 19 was symbolic. Although Moscow and Washington had declared that they had no plans to deploy previously banned intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe, the arms race had de facto resumed.

The main threat of missiles of this type is neither the nuclear warhead that they are capable of carrying, nor the effective distance. The primary danger is the reduction of the time to the target. This undermines the very foundations of nuclear deterrence, which in its turn is a key component of strategic stability. The doctrine of mutual assured destruction keeps the opposing sides from attacking because they are unable to completely disable each other with their first strike.

Intercontinental ballistic missiles are detected and tracked by missile early warning systems and the time taken to reach the target allows full evaluation of the situation and for the ordering of a retaliatory counter-strike where deemed appropriate. The time to the target for medium-range missiles launched from NATO’s easternmost flank to Moscow is about 5 minutes, which makes it extremely difficult for the Russians to take a decision on a retaliatory strike. Such missiles are also much harder to intercept meaning that it is easier to deliver a first “decapitation” strike against headquarters, bunkers, protected command posts, communication centers, and the like. This, in its turn, leads to nuclear powers considering a preventive nuclear strike policy, which makes the international situation extremely unpredictable and dangerous. The likelihood of an accidental initiation of a full-scale nuclear war increases dramatically. There is also the additional threat of cyberstrikes capable of blocking early warning systems or triggering false alarms.

That was precisely the reason why the deployment by the USSR and the U.S. of intermediate- and short-range missiles in Europe in the early 1980s provoked a serious international crisis and ultimately led to the decision to eliminate such missiles as a class.

Given the high level of distrust and the weak interest of major global players in getting back to arms control, it would be highly unrealistic to expect both the revival of the INF Treaty and the beginning of negotiations over an upgraded system of agreements that would be based upon the new reality. Historical experience suggests that only a severe crisis can pave the way for negotiations of this kind, like the Cuban Missile Crisis or the missile crisis of the early 1980s already referred to. The long-lasting habit of living in the absence of the threat of a major war, which is characteristic of Western countries and Russia, results in both sides underestimating the danger of militarization and provocation, including at the level of propaganda and political rhetoric.

The willingness of one or both sides to make substantial concessions, as was the case, for example, with the USSR back in 1987, must become an additional factor. However, there are no signs of such willingness at the moment.

Regional security trends

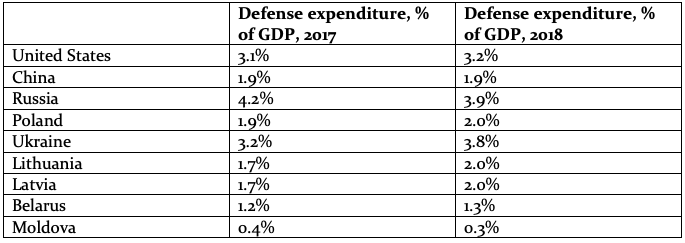

The main regional security trend is the militarization of the region and the resumption of the arms race. This trend reflects not only the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, but also the global trend towards increased defense spending and growing confrontation in international politics. The number and scale of military exercises are also growing, both within NATO and the CSTO.

According to SIPRI, USD 1,822 billion was spent on arms worldwide in 2018, an increase of 2.6% from the previous year. The U.S. spent 4.6% more than in 2017, driven by its comprehensive army modernization program, and its military budget for 2018 amounts to USD 648.8 billion. China ranks second with USD 250 billion spent on armaments and modernization of its army. Russia has mostly completed its rearmament program and, therefore, in 2018 its military expenditure was slightly lower than in previous years. It ranked sixth and for the first time in 12 years, it was outside the top-5. Nevertheless, its military expenditure remains high in terms of its GDP.

Source: SIPRI database

Some developments of the past 18 months demonstrate not only the increase in defense spending in the region, but also the commencement of the regional arms race, as new weapons and military equipment are accepted for service and new military units are deployed.

For example, Russia deployed the most recent Samarkand radio-electronic warfare systems in its western regions, significantly increased its missile weaponry and attack UAVs in the inventory, and completed the formation of a tank regiment and two additional aviation regiments in the Kaliningrad Region. Furthermore, a new tank regiment was deployed in the Smolensk Region. In addition, further buildup of forces in the Western Military District was announced, alongside the strengthening of the Russian military grouping in Crimea.

Poland announced the beginning of a large-scale rearmament program for the period up to 2026, worth a total of USD 48.8 billion. Previously, Poland purchased Patriot SAM systems and HIMARS high mobility artillery rocket systems (capable of launching munitions with a range of up to 300 km) from the U.S. and is now discussing purchases of the latest U.S. F-35 fifth-generation jet fighters. The start of 2019 saw the formation of the 18th Mechanized Division of the Polish Army. An agreement was reached with the U.S. to increase the U.S. military presence in Poland.

The Lithuanian army received the PzH 2000 self-propelled howitzers and Germany approved new investments in the development of the Lithuanian military infrastructure, as well as in the completion of the modernization of the firing range in Pabradė. The Lithuanian Iron Wolf mechanized infantry brigade was affiliated with a German panzer division and de facto came under German command. Meanwhile, NATO Headquarters Multinational Division North was established in Latvia.

Ukraine deployed the 61st Jager infantry brigade of its Armed Forces on the border with Belarus. The seizure of Ukrainian naval vessels by the Russian coastguard in the Sea of Azov at the end of 2018 and the subsequent martial law in Ukraine became another manifestation of the explosive situation in Eastern Europe.

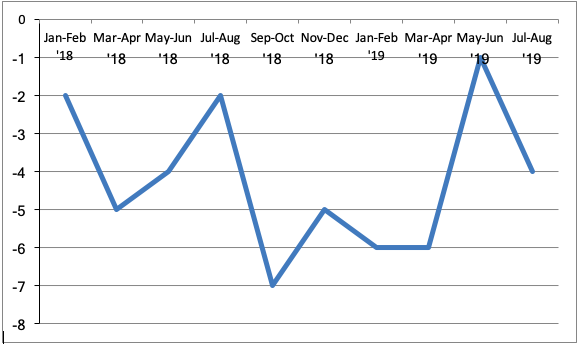

Changes in the level of regional tension

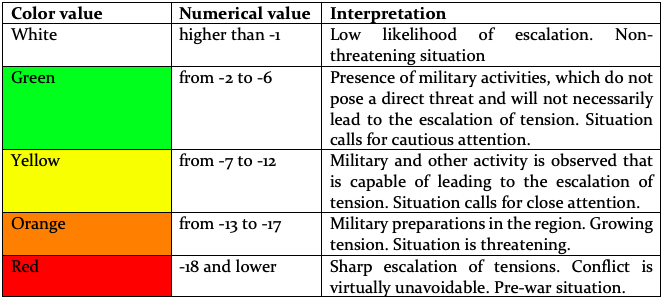

As part of the Minsk Barometer foreign policy and security monitoring, Minsk Dialogue experts have compiled the regional tension index since the start of 2018. The index tracks the level and quality of military activities along the perimeter of the Belarusian borders. Final evaluation uses a modified version of the Torino scale which was initially introduced to assess the probability of a space object to hit the Earth. The results of the monitoring confirm that the militarization of the region around Belarus continues and is aggravated by the global confrontation between the U.S. and Russia, while the current security situation remains rather stable. There are not enough armaments and deployed contingents for full-scale offensive operations.

Level of regional tensions

Regional security tension scale

Belarus’s adaptation

Against this backdrop, Belarus does not plan any significant changes in its military policy, but is gradually adapting to the current realities in the region. Minsk relies on its available domestic resources in ensuring security while maintaining its collective defense commitments within the CSTO and promoting confidence-building measures with its neighboring countries. The Belarusian government is consistently looking for ways to cooperate with NATO and partner states of NATO (primarily Ukraine). This policy is being implemented amid NATO’s growing presence and buildup of its infrastructure along Belarus’s northern and western borders.

The Belarusian leadership is developing cooperation with Western partners and promoting Belarus’s participation in peacekeeping operations. It has proposed its involvement in a peacekeeping mission in eastern Ukraine. Progress towards these promising tasks is another component of the gradual reform of the army.

Belarus has initiated a major security dialogue as a way out of the current situation in international relations, aimed at ultimately developing new fundamental rules for interstate cooperation. Under the circumstances of the “critical disjuncture” and growing contradictions, this initiative may seem excessively ambitious and devoid of substance — a clear interest in the side of key world powers. However, in these conditions, it is small states that are in the most vulnerable position, and therefore most interested in fair and transparent rules of the game. It is logical for them to take a proactive stance in international forums, thereby ensuring a critical mass necessary to start negotiations for a new system of international treaties in arms control and peaceful settlement of conflicts.

The expert dialogue that has started in this area, including within the framework of the Minsk Dialogue Forum, can serve as an important preparatory phase in this direction and provide decision-makers with substantive groundwork for launching the process at the policy level.