Before the seminar (on 7 September 2017), the international conference The Future of the Eastern Partnership amid Growing Regional Turbulence took place. It was jointly organised by the Minsk Dialogue Track-II Initiative and the Estonian Presidency in the Council of the EU (and supported by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation). Information obtained during the conference was summarised and used during the scenario-planning exercise. Two reports (a publicly available one and a closed one) were produced as a result of the seminar.

Seminar Participants

- Sergey Kizima – Chair of International Relations, Public Administration Academy under the aegis of the President of the Republic of Belarus

- Wolfgang Sender – Country Director Belarus, Konrad Adenauer Foundation (Germany)

- Aliaksandr Shpakouski – Director, “Aktualnaya kontseptsiya” Centre

- Viachaslau Paznyak – Professor, European Humanities University

- Aliaksandr Filipau – Director of the Advanced Training and Further Education Institute – Dean of the Faculty of Extended Education, Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts; Expert, Discussion and Analytical Society Liberal Club

- Roza Turarbekova – Associate Professor, Faculty of Interational Relations, Belarusian State University

- Dzianis Melyantsou – Belarus's Foreign Policy Programme Coordinator, Minsk Dialogue Track-II Initiative

- Yauheni Preiherman – Head, Minsk Dialogue Track-II Initiative

Christina Johannesson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Kingdom of Sweden to the Republic of Belarus, and Mihal Chabros, Counsellor of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in the Republic of Belarus, addressed the seminar participants with thematic contributions.

Eastern Partnership Eight Years after the Prague Summit

1. The Eastern Partnership (EaP) was suggested by Poland and Sweden as a geopolitical initiative to balance the Southern dimension in EU foreign policy. The initial idea promoted by Warsaw and Stockholm foresaw the preparation of the six partner countries for EU membership, as well as a possibility for Russia to join. Later, after the Russian-Georgian war, Russia acquired the reputation of a threat to the security of the neighbours of the EU. As a result, the EaP, instead of becoming subordinate to Russia-EU relations, transformed into a competing project. This predetermined Russia’s hostile attitude towards the EaP. Also, the EU put aside the goal of preparing the partner states for membership. This somewhat emptied the project.

2. Today, the fundamental problems of the EaP remain unresolved:

- The EU applies the same principles to all partner countries, differences in their political regimes (and political cultures) and integration aspirations notwithstanding. This results, in particular, in the dysfunction of the conditionality approach when applied to countries with no ambition of close integration with the EU. Thus, the EaP remains “lost” somewhere in-between EU enlargement and the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP).

- There is no clear understanding and definition of what exactly the EU tries to promote in the partner countries under the names of “shared values” and “shared ownership”.

- In its relations with third countries, the EU applies a vertical approach, i.e. the one based on unilaterally imposed standards, rules, and conditions, which in itself contradicts the very idea of partnership. The documents of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) emphasise that the partnership should be based exclusively on the values of the EU. As a result, contributions to the development of cooperation principles and rules by partner states are minimal. This a priori decreases the chances of successful cooperation.

3. The goals of the EaP are often contradictory. In particular, the advancement of security and economic cooperation, on the one hand, and values – on the other. The initiative’s objectives remain “blurred”, without specific indicators along many directions. Recently, gradual transformation of the EaP has taken place, which has partially led to further “blurring” of its goals and objectives. At least one goal of the EaP is no longer applicable to Belarus: the mandate to conduct free trade negotiations is now in the hands of the Eurasian Economic Commission, not Minsk.

4. The evolution of the EaP and ENP in general, as well as the EU’s systemic refusal to formulate the EaP’s ultimate goals and objectives (particularly in relation to Belarus) have led to the EaP being neither a geopolitical nor an infrastructural initiative. Also, it is neither focused on values nor on interests. The EU’s regional initiatives look more like symbolic ones aimed at presenting the EU as a global actor. As the EU sees itself as a global actor, it has to offer large-scale projects, even when it cannot implement them. However, these projects lack a strategic basis.

5. Another problem has to do with the fact that various stakeholders in the EU and partner states interpret the EaP terminology differently. States often speak different languages even when their interests coincide.

6. The concept of constructivism used by the EU (i.e. the construction of the neighbourhood in accordance with the EU’s own standards in ideas) has proved futile. Constructivism, without proper strategic footing, has lost to harsh realism. Moreover, constructivism led to armed conflicts, as it had not taken into consideration the realities and specific processes in the post-Soviet space. Behind its own political and ideological constructs, the EU did not spot the conflict in Ukraine emerging.

7. As a matter of fact, the EaP is being divided into three groups, depending on the intensity of the partner countries’ cooperation with the EU and their aspirations for further integration. The first group consists of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, which have concluded association agreements with Brussels. The second one includes Azerbaijan and Armenia. These states are about to sign new bilateral agreements with the EU. Finally, Belarus is in the third group, as the only EaP country which still has no framework agreement with the EU.

8. The new edition of the EU Global Strategy was adopted in 2016 and introduced the principle of resilience as the cornerstone of crisis management and the EU’s relations with partner countries. The principle is being built into the EaP but without a specified understanding of its meaning and implications.

The Positions of Key Actors among the EU Member States

1. Besides Poland and Sweden, the initiators of the Eastern Partnership, today the group of EaP supporters includes the Netherlands, the Baltic states, Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and (depending on circumstances) Bulgaria. Before the Brexit story began, the UK was also an EaP supporter. Germany plays a key role for the EaP.

2. Both Germany and Poland have come to the conclusion that the geopolitical context in which the EaP develops has to be taken into account. This explains recent discussions about more realistic and less ambitious goals. In June 2017, the Bundestag passed a resolution on the EaP, in which it reaffirmed the importance of the initiative for the modernisation of the partner states and also underlined progress in the relations with Belarus.

3. The EaP, as a balancer of the Southern dimension of EU foreign policy, remains important for Poland and sits high on Warsaw’s foreign policy agenda. Poland emphasises the activation of its bilateral relations with Belarus; however, it also sees a “wall”, i.e. systemic limitations, in these relations. Belarusian-Polish relations now encompass more topics, but the EaP agenda as such does not dominate there.

4. Poland is determined to promote connectivity in the EaP. It is particularly interested in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative. Work aimed at improving connectivity with Belarusian partners is underway. For example, the E-40 project is seen as a useful connecting link between the EU and its Eastern partners.

5. For Sweden, the EaP also remains strategic, as it deems necessary to sustain balance between the Southern and Eastern dimensions in the EU. Sweden traditionally advances a value-driven agenda in the EaP and its own foreign policy. Stockholm’s position is based on the argument that common values should facilitate investment growth in the region, as relations between states will have a more stable and predictable footing.

6. Sweden suggests that the EaP be incorporated in the broader context of global initiatives. For example, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Paris Climate Agreements, etc. This should facilitate new synergies, as well as balance the interests and possibilities of different actors.

Belarus and Other EaP Participating States

1. East European and South Caucasian states participating in the EaP are objectively interested in developing relations not only with the EU but with one another as well. Regular contacts and project-based cooperation within the EaP framework help to intensify and diversify intra-regional cooperation. At the same time, geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West are “tearing the region apart” because states see their interests differently and, hence, adhere to different strategies in building relations with the competing centres of power.

2. The escalation of geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West also impacts negatively the pace and effectiveness of reforms in the EaP countries. In some of them, elites do not dare to undertake reforms as they do not envision prospects for enhanced economic growth amid regional instability and mutual sanctions regimes. As a result, they avoid potentially risky large-scale reforms and prefer to muddle through, which seems a less risky strategy in the short-term. In other countries of the region, elites use the fact of geopolitical confrontation as an excuse for the lack of progress with reforms.

3. The European principle of inclusiveness does not work in relation to Belarus. The country is excluded from many programmes, its voice is not heard in some important discussions. Multiple examples of double standards (at least, as they are interpreted by the Belarusian government and society) also undermine Minsk’s trust to the EU.

4. The EU’s policy to engage Belarus has effectively been declarative. It lacks stable and explicit mechanisms of engagement. The “roadmap” of cooperation has a general political, rather than practically specified, character. The absence of specified prospects for improving relations weakens the interest in the European vector among Belarusian elites.

5. Lack of information remains another problem of the EaP in Belarus. Even among stakeholders (central and regional government and self-governance institutions, expert community, and NGOs), there is lack of understanding of opportunities and cooperation mechanisms within the EaP. Little information is available about ongoing projects, as well as which cooperation projects are part of the EaP and what is done along the bilateral track. Not surprisingly, research has shown that Belarusians perceive the EaP with most pessimism among all partner countries.

6. At the same time, Belarus-EU relations have actually gone beyond the documents that set the frameworks for both the EaP and bilateral tracks. In practice, bilateralisation and concentration on “doable” tasks are taking place.

Scenarios of Future Developments in the Eastern Partnership Region and their Implications for Belarus

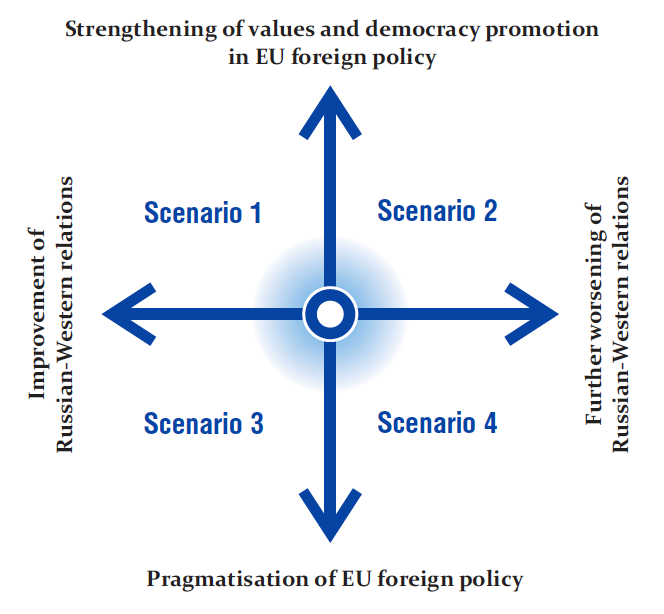

The participants of the seminar analysed a number of critical uncertainties (independent variables) which, with a high degree of probability, will determine medium-term developments in the EaP region. The scenario-building exercise revealed two most significant pairs of critical uncertainties:

- Strengthening of values and democracy promotion in EU foreign policy versus Pragmatisation of EU foreign policy;

- Improvement of Russian-Western relations versus Further worsening of Russian-Western relations.

Also, the seminar participants singled out additional factors that can impact the scenarios and their implications for Belarus:

- strengthening OR weakening of the Eurasian integration;

- policies by such actors as China, Turkey, and the UK;

- internal dynamics in the EaP-6 countries (in particular, reform dynamics in Belarus).

On the basis of combinations of the most significant uncertainties and additional factors, the following four scenarios were singled out:

- Strengthening of the value-based approach in EU foreign policy with simultaneous improvements in EU-Russian relations (“Pragmatic idealism”).

- Strengthening of the value-based approach in EU foreign policy accompanied by further worsening of EU-Russian relations (“Cold War 2.0”).

- Pragmatisation of EU foreign policy with simultaneous improvements in EU-Russian relations (“Security above all”).

- Pragmatisation of EU foreign policy accompanied by further worsening of EU-Russian relations (“Bufferisation of the region”).

Scenario 1. “Pragmatic idealism”

Within this scenario, the EU will adhere to the promotion of democracy and human rights in its neighbourhood, all latest developments in the region and inside the EU notwithstanding. The EU Global Strategy and the overhauled ENP will, thus, remain the doctrinal documents governing EU foreign policy. At the same time, the scenario foresees gradual improvement in EU-Russian relations, which does not mean, however, that the EU will fully lift its sanctions and recognise the annexation of Crimea. The EU will just stick to a more pragmatic line in its policies towards Russia trying to avoid confrontation and cooperating with Moscow in areas of mutual interest. Such an approach should satisfy European businesses, as well as the EU’s main strategic partner – Washington.

For the EaP, this scenario will generally mean the continuation of existing trends, i.e. the preservation of the conditionality approach accompanied by gradual bilateralisation of the EU’s relations with partner states. European standards of human rights and governance will remain key criteria for productive cooperation with the EU. Yet, in order not to provoke Moscow, Brussels will not pursue new ambitious goals in terms of attracting partner states closer to the EU.

For Belarus, this scenario will imply the continuation of slow normalisation in the relations with the EU, without any major breakthroughs in the short-term. Criticism of domestic processes in Belarus on the part of EU institutions and difficult negotiations will go hand in hand with targeted bilateral and multilateral cooperation in areas of mutual interest.

Scenario 2. “Cold War 2.0”

The scenario will see attempts by the EU to democratise the neighbourhood and promote its values there against the background of further worsening Western-Russian relations. These characteristics remind the relations between the West and the USSR at the time of the Cold War. Were the scenario to unfold, the EaP region will turn into the territory where the interests of Russia and the EU clash, which will lead to heightened tensions on the European scale and destabilise the situation in the EaP states.

The logic of this scenario will demand that Brussels (as well as Moscow) offer proactive strategies toward neighbourhood states. This can result in an overhaul of the structure and goals of the EaP aimed at deepening the level of integration. However, internal dynamics in the EU and the new challenges it faces (instability, populism, migration, and Brexit, etc.) will still undermine membership prospects for the EaP states. More likely, the EaP agenda will include the following items: new infrastructural projects, broadening free trade regimes, more advanced bilateral political agreements, and deeper engagement of the partner states in existing EU policies (e.g. the Common Security and Defense Policy). This will only increase the divide between the so-called “EU-enthusiasts” (Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia) and “EU-skeptics” (Belarus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan).

For Belarus, the scenario will imply growing risks of cooperation with the EU and stagnation of the rapprochement process with the West in general. The alliance with Russia will remain top priority, which will require that Minsk factor Moscow’s position and fears in its foreign policy thinking. Under such circumstances, the current level of Belarus-EU cooperation, including within the EaP framework, seems the maximum of what is feasible.

Scenario 3. “Security above all”

According to this scenario, internal developments in the EU and the international environment (first of all, in the security realm) will force Brussels to conduct a more pragmatic policy towards both its immediate neighbourhood (the European Neighbourhood Policy) and Russia.

The scenario will also see sharp differentiation within the EaP, e.g. the EU will gradually drop its universal value-based approach and develop individual policies towards each partner country focusing on mutual interests in specific cooperation areas. This will dissolve the EaP in the European Neighbourhood Policy or even EU foreign policy in general. The idea of the EaP as a single entity will cease to exist, which will necessitate differentiated instruments and approaches in relations with the partner states.

For Belarus, such developments will ease tensions in relations with Brussels, which are caused by the conditionality approach and double standards on the part of the EU. At the same time, Minsk will have more freedom of manoeuvre as it will no longer be restricted by the confrontation between Russia and the EU. This scenario will open up opportunities for fully normalising relations with the EU and signing a bilateral framework agreement, as well as for implementing projects in areas of mutual interest (e.g. border security, combatting illegal trafficking, environmental protection, and the development of transit infrastructure, etc.).

Scenario 4. “Bufferisation of the region”

The fourth scenario is to a degree similar to the “Cold War 2.0.” scenario as it foresees further worsening of EU-Russian relations. Yet, its important difference is the EU’s refusal to prioritise values and democracy promotion in its foreign policy in the region. Instead, it will conduct a more pragmatic foreign policy towards immediate neighbours.

Security and stabilisation will feature highest on the EaP agenda. In fact, for the East European neighbours of the EU this will imply the creation of a “buffer zone” between the EU and Russia. The EU will try to avoid discussions about further integration of the partner states, in order not to provoke active and destabilising countermeasures on the Russian side (as was the case in Ukraine). Hence, Brussels will prefer to focus on infrastructural cooperation, as well as projects aimed at improving border security, developing sustainable economies, and strengthening the sovereignty of the neighbours. But because of numerous internal problems, the EU cannot be expected to significantly increase funding available within the EaP.

In the case of Belarus, the scenario will imply further gradual normalisation in the relations with the EU and the development of mutually beneficial pragmatic relations based primarily on trade and economic cooperation, as well as transit facilitation.

Most Probable Scenario

Against the background of existing trends inside the EU and in the international arena, Scenario 4 (“Bufferisation of the region”) looks most probable. Its key indicators are the following:

- The European Neighbourhood Policy will shift its focus from the promotion of values to the stabilisation and diversification of the neighbourhood;

- Normalisation of EU-Belarusian relations will continue despite the lack of what Brussels previously wanted to see as progress on human rights and democracy in Belarus;

- Security issues will be prioritised on the EU agenda;

- EU sanctions against Russia will remain in place;

- The EU will strengthen counter-measures against Russia in the fields of information and propaganda.Outlook and Recommendations

1. The EU offers only a general framework for relations with the EaP countries. This creates space for own initiatives by the partner states, which can (if they take right approaches) fill the overall framework with their priorities and interests. But they need to understand the peculiarities and limitations of the working mechanism of the EU, including its bureaucratic nature. For better coordination of their interests and initiatives, the six partner states should hold periodic multilateral consultations at the level of Ministries of Foreign Affairs. However, this can work only if the EaP region does not “fall apart”.

2. The differentiation principle has been declared and is becoming an integral part of discussions in the context of the EaP and ENP. Yet, it is important that a mode of its practical implementation be found which will satisfy all stakeholders. Otherwise, the EaP will continue to break into separate groups, which will ultimately result in the loss of the initiative’s regional component and question the need to preserve the “EU+6” format.

3. In order for the resilience principle, declared by the new EU Global Strategy, to work in the EaP countries, better understanding of the realities on the ground is needed. Country-specific expertise becomes a key factor of success.

4. It is crucial that the EU should not repeat its own mistakes, when its constructivism-driven policies ignored regional realities. Importantly, cooperation potential should be fully realised in both formats – between the EU and partners states and inside the EaP region. To this end, potential repercussions for regional cooperation of policies not directly related to the EaP should be taken into consideration. For instance, how do EU policies towards Russia impact the situation in the EaP states?

5. Amid growing regional turbulence, strategic communication between the EU and partner states becomes an asset. Due to the lack of sustainable and diversified channels of communication, small difficulties and misunderstandings can quickly transform into politically sensitive problems.

6. The most effective way to share European standards and experience is through applied project activities, which lead to practical results. In this respect, project work in the regions of the EaP partner states looks most promising and important. It is in the regions that the biggest void of competences and infrastructure is registered.

7. Both Belarus and the European Union are objectively interested in having Minsk upgraded from the EaP third group (the country without a framework agreement with the EU) to the second one (where it could join Armenia and Azerbaijan). For this to happen, negotiations about a bilateral agreement (a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement or a new type of agreement, like the ones that Kazakhstan or Armenia have negotiated) need to begin without preconditions. This would improve the overall level of mutual trust between Minsk and European capitals, infuse the relations with more predictability and tangible prospects, broaden the scope of cooperation, and facilitate the transfer of best practices and European standards. Moreover, it would have a positive impact on the Eastern Partnership as a whole, as it would make the initiative more solid and create additional conditions for the development of political and economic cooperation.

- Strengthening of the value-based approach in EU foreign policy with simultaneous improvements in EU-Russian relations (“Pragmatic idealism”).

- Strengthening of the value-based approach in EU foreign policy accompanied by further worsening of EU-Russian relations (“Cold War 2.0”).

- Pragmatisation of EU foreign policy with simultaneous improvements in EU-Russian relations (“Security above all”).

- Pragmatisation of EU foreign policy accompanied by further worsening of EU-Russian relations (“Bufferisation of the region”).